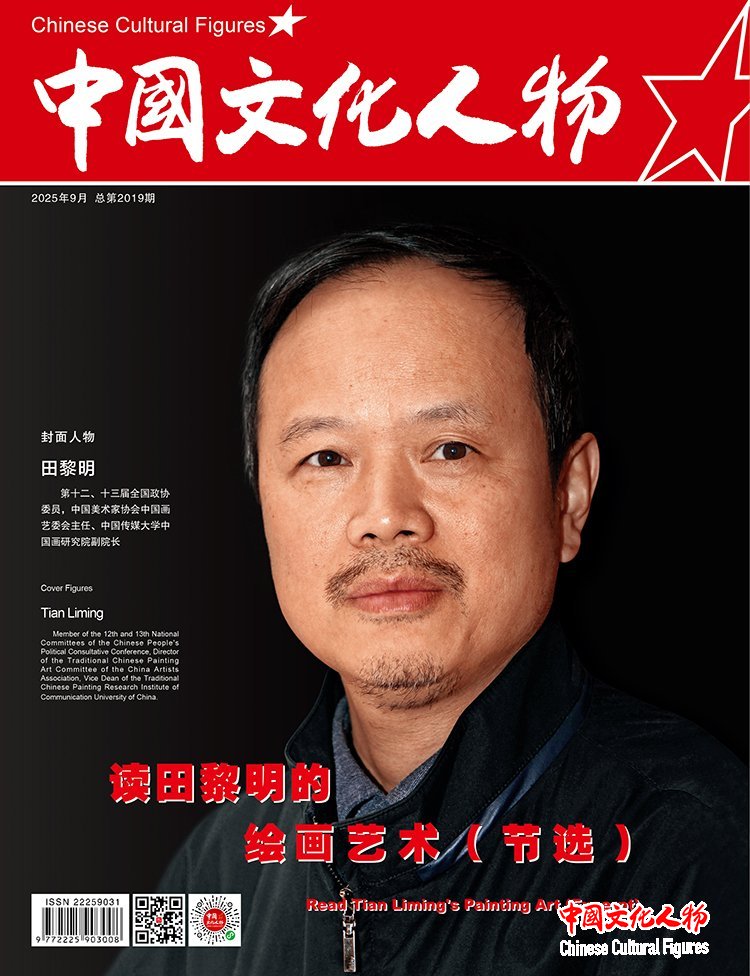

Cover Figures:Tian Liming Member of the 12th and 13th National Committees of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference, Director of the Traditional Chinese Painting Art Committee of the China Artists Association, Vice Dean of the Traditional Chinese Painting Research Institute of Communication University of China.

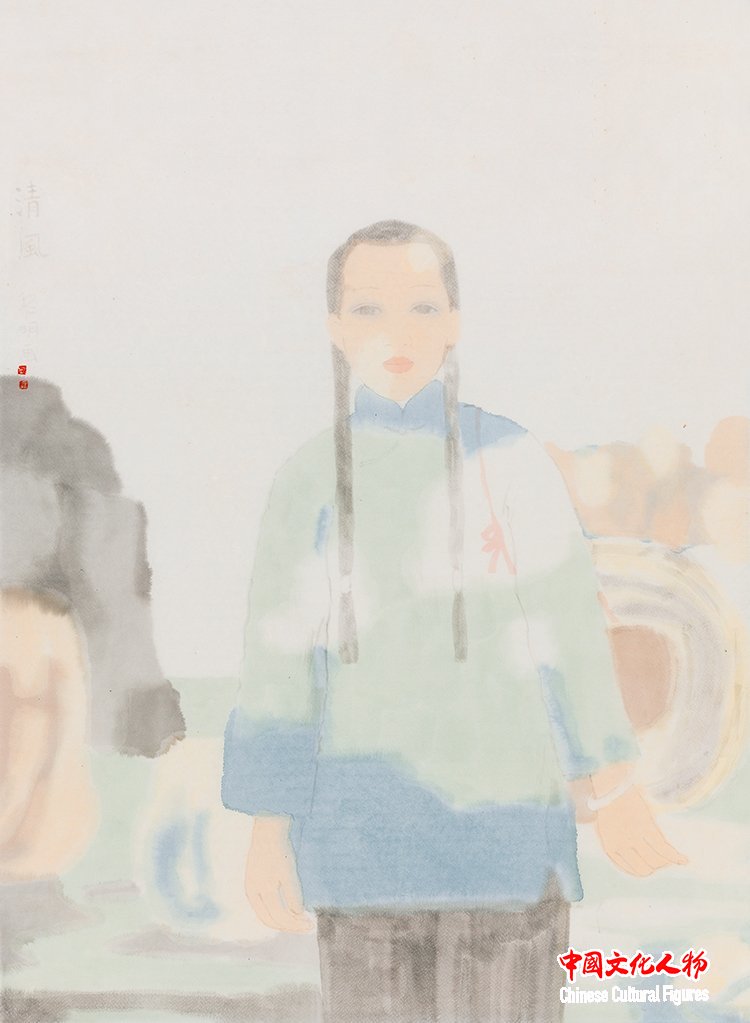

“Childhood Memories” (46×69cm) by Tian Liming in 2010

中国文化人物(主编 王保胜)田黎明的画之所以得到大家的好评,是因为他的画有自己的创意;更为重要的是,他的风格没有变质,仍然是中国画,而有的人的画虽有新意,却未必是中国画。说田黎明的画是中国画,主要有以下几个依据:首先,他的风格基本上是从传统的“没骨”来的,但却又把没骨法放大,即在没骨法的基础上有所发展,这样的发展在以前是很少见的。此外,田黎明又加入了光的因素,其中有一部分是外来的,但是他又把那种外来的光淡化了,形成了一种意象化的光,这就使这样的手法靠近了传统,实际上,这是对传统没骨法的一种丰富和发展。

“笔简意足”的没骨法

一般而言,没骨法分为两种,一种是色彩的没骨,一种是水墨的没骨。宋代有一《百花图卷》,是画得很工的没骨。史载梁时张僧繇始用没骨之法,系从天竺传来,清代王学浩认为此法始于唐代杨升,历史上山水画也有这种没骨,完全用颜色来画山水,人物画也有,像梁楷的那种风格基本上就是没骨法。没骨比较突出的发展是到了恽南田以后,恽南田画花卉基本是采用没骨的方法,在这点上做得非常突出。在我看来,田黎明绘画的样式、风格、趣味、格调等全都是围绕着没骨法来进行的,比如在88年第一届中国画研究院主办的水墨展上,他获奖的那几幅作品,非常明显,全都是用没骨的方法完成的,如《带着草帽的老头》,虽然非常简单,但全都采用了没骨的手段。后来他又在没骨的基础上融入了淡墨、淡色,加入了光的因素,之后又加了一些用笔的方法,这样在没骨中又融入了笔法,这些笔法中有书写的意味,但显现的不是勾线,而是块面结构。

田黎明成熟期的作品,人物造型上的基本特征可以用“简朴”二字概括。他的作品,虽属“简”笔,即“笔简意足”,有意弱化了人物的个性特征,忽略人物在特定环境中的典型情态,而将他们的形象风格化,并由这种风格化的造型暗示出一种内在的“意”来。这种风格特质和背后的意蕴,正可以用“简朴”的“朴”字概括。

来自自然源自心灵的光

有的评论说,田黎明对光的刻画与印象派有关,这似乎并不准确。印象派画家重视光,田黎明也重视光,这一点是相近的,但田黎明对光的理解、对光的处理,与印象派对光的处理完全不相干。在印象派画家那里,光即是自然的光,与色不分离,是色的来源,不同时间、不同空间的光照其色彩也不同;而在田黎明这里,光来于自然,也源自于心灵,光与色没有必然的联系。简言之,田黎明画中的光,主要是根据画意之需“杜撰”出来的,与印象派的描绘自然光色是两回事。

田黎明的画特别和谐,可以说是一种天人合一之作,这种境界是西方艺术素描,特别是西方现代艺术素描中所没有的,它们(西方现代艺术)基本上都是矛盾、冲突、对抗、激烈、变形,丑怪、不安的一种状态。而田黎明的这种和谐之美是中国传统的东西,是传统的一种精神,但是在形式上又有一些水彩的因素。他从印象派的光的表现上受到启发,但是他并没有纯粹模仿印象派的东西,印象派的光是用一种光色的方法,像莫奈画的草垛,就是描绘从早上到晚上光的变化。实际上,印象派非常接近自然规律,对光进行很科学的分析,比如描绘傍晚的光的时候,可能就增加了紫色调,而中午的光黄调子比较多,早上的光蓝调子比较多,再加入一些环境色。印象派的产生与科学的发展尤其是光学的发展有着密切的关系。虽然田黎明吸收了其中的一些因素,但是他有一种创作性,并且他不是突然发生变化的,即不是心血来潮——看着这个东西马上就做出来了,而是选择了这条道路以后,一点一点地往前推,是一种渐变性的。并且对于外来的因素也是一点一点地吸收,这是与他的个性有关系的。

田黎明画作中的光,有四个方面值得关注:首先,通过斑驳阳光的感觉(只是“感觉”而已),赋予画面以自然生命的活泼,这活泼与人物的静谧形成照应。其二,他们带给画面一种扑朔迷离的气氛,这气氛恰好烘托人物形象的“简朴”,令人觉得那是跟气象万千的大自然相与共的“简朴”。其三,它们大大小小洒满画幅,一方面对空间纵深感有所消解,另一方面又增加了空间的丰富性,甚至造成一种光照无常、欲真又幻的效果。其四,它们也和人物造型的“简朴”一样,比写实性描绘更具有“间离效果”,即距离物的真实世界更远一些,从而有助于把观者带入画家所醉心的意境即精神世界之中。

郎绍君(中国艺术研究院研究员、美术史论家)

田黎明

1955年生于北京。1991年毕业于中央美术学院中国画系。

第十二、十三届全国政协委员,中国美术家协会中国画艺委会主任、中国艺术研究院国画院教授、中国传媒大学中国画研究院副院长。曾任中国国家画院副院长、中国艺术研究院副院长兼研究生院院长。

擅长水墨人物画,以人与自然的和谐为创作法则,以“和”的审美理想融中国传统儒、道、释构成了其作品追寻平淡天真的审美理念。在多年创作中,逐步探索并系统地延伸和发展了传统绘画中的没骨画,以阳光、空气、水为主题,呈现出鲜活的时代感,形成了自己的绘画理念和艺术风格,其都市系列作品则指向对都市文化的思考, 呈现人沉浸于都市状态之中的当代图式;近年新作则以中国画写意在当代为理念的重大主题创作,展现了绘画语言的新风貌。

Chinese Cultural Figures (Chief Editor: Wang Baosheng) Tian Liming’s paintings have gained widespread acclaim for their original creativity. More importantly, his style remains an authentic form of Chinese painting, unlike some works that appear innovative yet deviate from the traditional essence. Tian’s art is recognized as genuine Chinese painting for three key reasons: First, he has expanded the application of the traditional “mogu” technique through innovative development, a rare approach in previous practice. Second, he incorporates light elements, some of which are borrowed from external sources, yet he subtly softens these artificial radiances, turning them into an impressionistic glow. This synthesis brings his technique closer to tradition while enriching and advancing the classical mogu method.

The mogu method of “writing with a few strokes”

The mogu technique generally exists in two forms: color-based and ink-wash. The Song dynasty masterpiece Scroll of Hundred Flowers exemplifies meticulous mogu execution. According to historical records, Zhang Sengyou introduced this method from India during the Liang Dynasty. However, Qing scholar Wang Xuehao traced its origins back to a Tang Dynasty artist named Yang Sheng. The mogu technique flourished in landscape painting with pure colors, and figure painters like Liang Kai used it extensively. Mogu artistry reached its zenith with Yun Nantian, whose floral paintings became iconic through this approach. In my view, Tian Liming’s artistic style, aesthetic sensibility, and creative vision are entirely rooted in mogu techniques. His award-winning work at the 1988 China National Academy of Painting exhibition, such as the minimalist “Old Man in Straw Hat”, demonstrates this methodology. Later, he innovated by blending light ink washes, subtle color gradations, and luminous effects with calligraphic brushwork. These strokes, imbued with literary brushmanship, create layered compositions rather than rigid outlines.

Tian Liming’s mature works are characterized by their “simplicity” in figure modeling. Employing the principle of “concise brushwork with profound meaning,” he intentionally downplays individual traits and abstracts typical behaviors from specific contexts. This artistic approach transforms characters into stylized forms that hint at an underlying “essence.” This distinctive style and its implied philosophical depth perfectly embody the essence of “simplicity” through its rustic simplicity.

Light from nature and the heart

Some critics argue that Tian Liming’s portrayal of light is related to Impressionism, but this seems inaccurate. Although Impressionist painters valued light and Tian shares this common ground, his understanding and treatment of light are entirely unrelated to the Impressionists’ approach. For Impressionists, light is the essence of nature, inseparable from color and serving as its source, varying with time and space. In contrast, Tian’s light originates from both nature and the mind and has no inherent connection to color. In short, the light in Tian’s paintings is fabricated for artistic expression and is fundamentally different from the way Impressionists depicted natural light and color.

Tian Liming’s paintings are particularly harmonious. One might say they represent unity between heaven and humanity. This concept is absent from Western art, especially modern Western art, which is characterized by contradiction, conflict, confrontation, intensity, distortion, grotesqueness, and unease. In contrast, the harmonious beauty of Tian’s works embodies the essence of Chinese tradition, representing a spiritual legacy while incorporating watercolor techniques. Inspired by Impressionist techniques of light expression, Tian Liming did not merely imitate Impressionism. The Impressionists employed a method of light and color, as seen in Monet’s haystack paintings, which depict changes in light from morning to night. In reality, Impressionism adheres closely to natural laws through the scientific analysis of light. For example, when depicting evening light, they might use more purple tones; midday light, more yellowish hues; and morning light, predominantly blue tones supplemented by environmental colors. The emergence of Impressionism is closely linked to scientific advancements, particularly in optics. Although Tian Liming absorbed some of these elements, he demonstrated creative autonomy, advancing his artistic path gradually through incremental refinement rather than creating spontaneously. His gradual assimilation of external influences also reflects his individuality. Four aspects of the light in Tian Liming’s works deserve attention. First, he imbues the canvas with natural vitality through the sensation of dappled sunlight, creating a dynamic interplay between the painting’s liveliness and the subjects’ serenity. Second, these elements imbue the composition with an enigmatic atmosphere that accentuates the characters ‘”simplicity,” creating an impression of harmony with nature’s boundless grandeur. Third, their scattered distribution across the canvas—in both large and small sizes—deconstructs spatial depth while enriching the visual dimension. This produces an ethereal effect in which light flickers between reality and illusion. Fourth, mirroring the characters’ minimalist design, these elements create a stronger sense of alienation than realistic depictions do. They distance viewers from the tangible world and transport them into the artist’s spiritual realm—a realm of contemplative beauty that invites reflection.

Lang Shaojun (Researcher, Chinese Academy of Art, art historian)

Tian Liming

He was born in Beijing in 1955 and graduated from the Department of Traditional Chinese Painting at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in 1991.

He is member of the 12th and 13th National Committees of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), Director of the Traditional Chinese Painting Art Committee of the China Artists Association, Professor at the Traditional Chinese Painting Academy of the China National Academy of Arts, and Vice Dean of the Traditional Chinese Painting Research Institute of Communication University of China. He once served as Vice President of the China National Academy of Painting, and Vice President of the China National Academy of Arts, and concurrently held the post of Dean of its Graduate School.

He specializes in ink figure painting and adheres to the principle of harmony between humanity and nature in his creative practice. He integrates the aesthetic ideal of “harmony” with traditional Chinese Confucian, Taoist, and Buddhist philosophies, pursuing a serene and natural aesthetic philosophy in his works. After years of artistic exploration, he has systematically developed the traditional mogu painting technique, using sunlight, air, and water as themes to convey a vibrant sense of contemporary sensibility. This process has shaped his unique artistic vision and style. His urban-themed series reflects contemplations on metropolitan culture, presenting modern patterns of people immersed in urban environments. His recent works focus on significant themes rooted in contemporary Chinese freehand brushwork, showcasing new dimensions in the language of painting.

文化大家

文化大家