封面人物: 刘万鸣 第十三、十四届全国政协委员,中国美术家协会副主席、中国国家画院院长

Cover Figures:Liu Wanming Member of the 13th and 14th National Committees of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference, Vice Chairman of the China Artists Association, President of the China National Academy of Painting.

中国文化人物主编 王保胜/摄影报道

峦音 45×45cm 2025 刘万鸣作品

“Luan Yin”( 45×45cm) by Liu Wanming in 2025

大吉 42×30cm 2025 刘万鸣作品

“Great Fortune” (42×30cm) by Liu Wanming in 2025

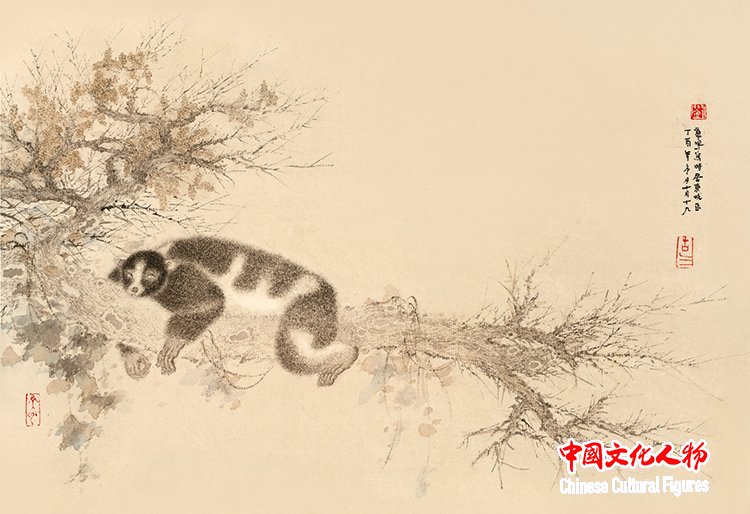

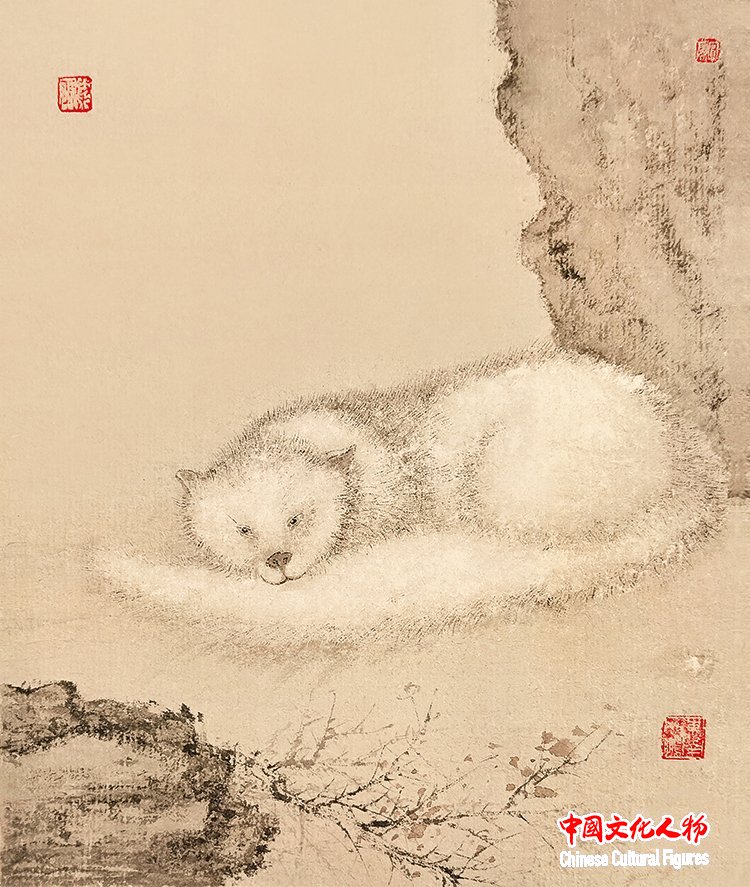

清闲 30×45cm 2017 刘万鸣作品

“Leisure” (30×45cm) by Liu Wanming in 2017

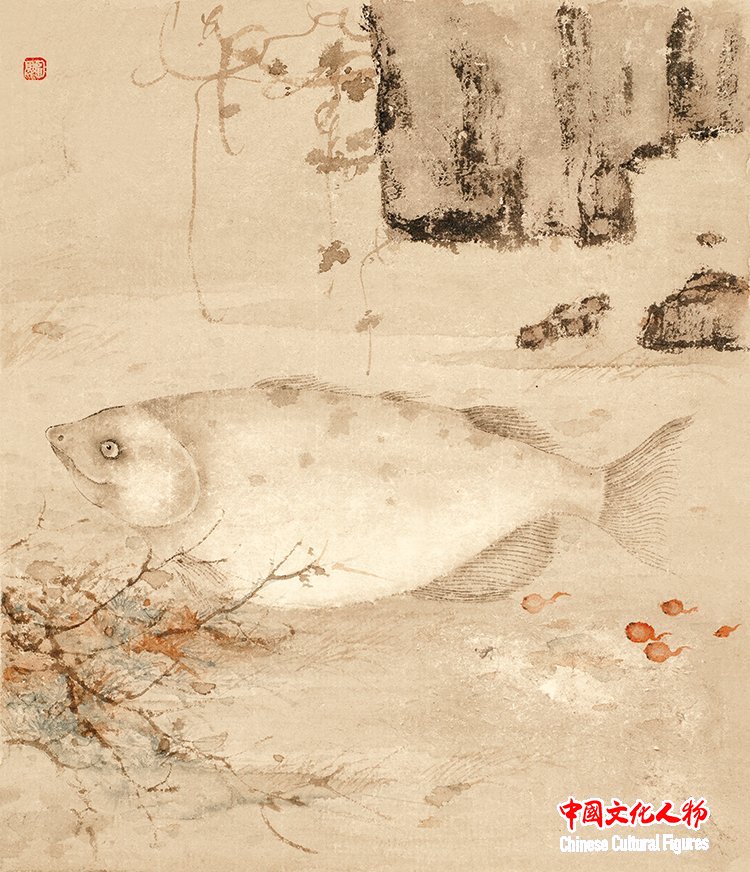

静潭 20×17cm 2025 刘万鸣作品

“Quiet Pond” (20×17cm) by Liu Wanming in 2025

忘机 45×33cm 2025 刘万鸣作品

“Freedom from Cunning Thoughts” (45×33cm) by Liu Wanming in 2025

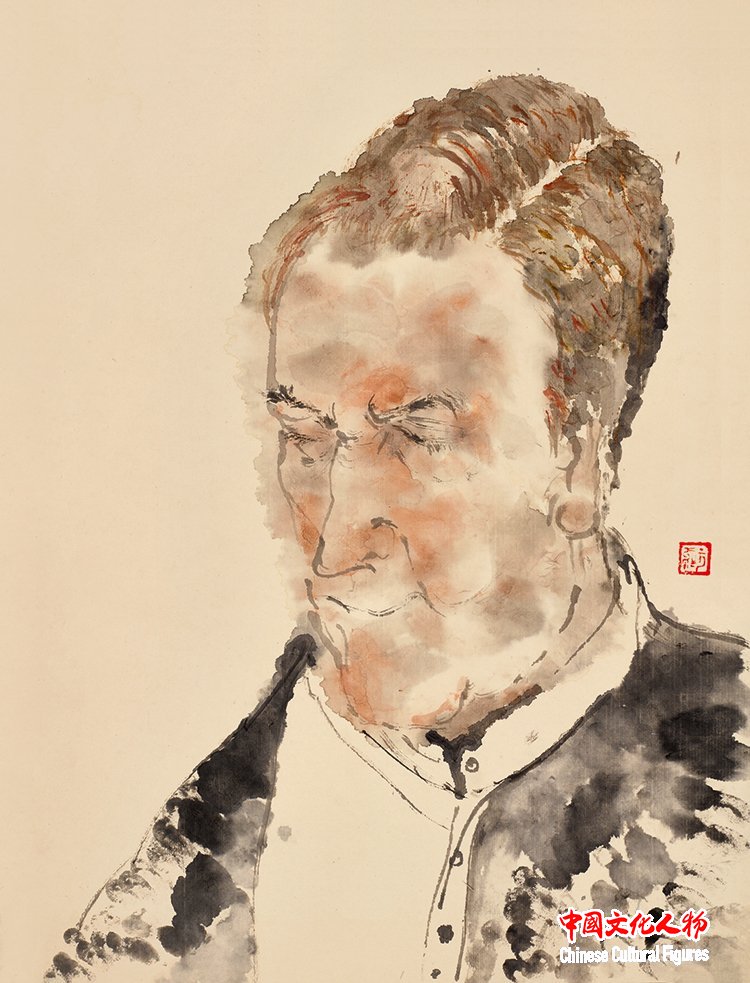

肖像写生 45×33cm 2025 刘万鸣作品

“Portrait Sketching” (45×33cm) by Liu Wanming in 2025

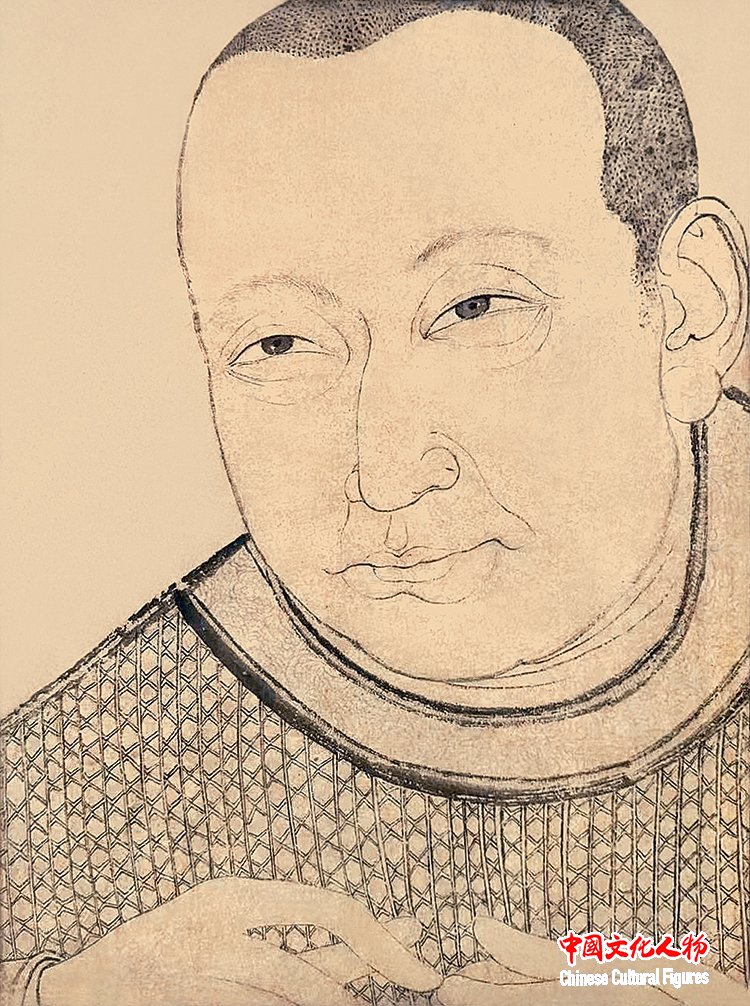

人物 38×30cm 2025 刘万鸣作品

“Character” (38×30cm) by Liu Wanming in 2025

雨润石隐 45×45cm 2025 刘万鸣作品

“The Rain Moistens the Hidden Stones” (45×45cm) by Liu Wanming in 2025

大吉祥 40×35cm 2020 刘万鸣作品

“Great Auspiciousness” (40×35cm) by Liu Wanming in 2020

秋籁 20×17cm 2025 刘万鸣作品

“Sounds of Autumn” (20×17cm) by Liu Wanming in 2025

中国文化人物(主编 王保胜)凡能传世之画,必有一种“气”充畅其间,就宋元传统绘画而论,则以静气、清气、苍莽之气为高。画者坚守己志,万物不足以搅挠其心,涵养日久,必有静气生发。清气乃光明正大之气,苍莽之气乃浩远莽厚之气,二者皆不易得。静气和清气,必有作者修养的高度在内;而苍莽之气见于笔下者,则必有作者修练的功力在内,这修练的基础还在于作者对传统艺术的理解力,功力和修养深厚之画者方能有苍莽之气。尝见很多画人,因对传统无所理解,则把恶墨俗笔作为追求目标,则愈练愈离传统愈远,艺术的成分也愈少。另一种不理解再加之修养不够,则以形似为目的。媲红配绿,工描细染,结果功愈细而格愈卑。此二者皆不足以论画,更不可能把画画好。

刘万鸣的画,造型严谨,用笔潇洒,内蕴无穷而变化丰富。他以宋元传统为根基。宋画严谨精确,浑朴厚重,形神兼备,且庄严大气;元画潇洒藴藉,轻松舒畅,而富书卷气。万鸣的画既有宋画之严谨精确、庄严大气,又有元画之潇洒藴藉和书卷气。他集众所善,以为己有;更自立意,专为一家。其画中有一种很强的静气、清气和苍莽之气,格调高古而新颖,代表着中国花鸟画发展的一种特别而实在的高度。

刘万鸣成熟的画法也是经历了几个过程。开始他的画基本上是流行画法中的宋元法。比如他先前画的树叶,以大笔湿墨分浓淡挥洒而成,画鸟也如此。这其实是流行画法,更多的是吸收了天津几位名家的笔法,当然也增加一些自己的笔法。他的线条大多源于元。万鸣是学者型画家,他研究过历代画论,也研究过历代画法。师宋主要师法北宋,他认为南宋气就弱了。北宋和元代的绘画中都很少有大片的墨,元不但没有大片的墨,也没有太重的墨。周亮工说:“画有繁减,乃论笔墨,非论境界也。北宋人千丘万壑,无一笔不简;元人枯枝瘦石,无一笔不繁。”元人用干墨,缓缓下笔,借以书法笔意,轻重、疾徐,提按转折,一笔之中,变化多端,藴藉无穷,故笔画虽简,而线条内涵无穷,即“无一笔不繁”。宋人画山,如范宽之《溪山行旅》,千笔万笔,每一笔实实在在,但也很简,即内在变化不多。比较而言,元人的线条比宋人更进一步。明代后期文人画家之所以看不起浙派画家,就是因为浙派画家用大笔湿墨挥洒,外呈气势,而内涵不足。刘万鸣研究宋元画法之后,深明此理。他的画保留了宋法的严谨,形神兼备,但用元人笔法,松而柔,缓缓下笔。加之他深厚的碑学底子,书法笔意变化多端,实中见虚,内涵丰富。而且层层积染,层次多而厚重。他的线条,以颤斫之笔,无一实笔,无一虚笔,皆在虚实之间,即古人说的,实笔虚之,虚笔实之,这是有难度的。万鸣在明理而后而知其妙,从而形成了他的独特画风。

万鸣的独到画法,下笔不过分激动,不费神;不精工细描,不费心机,这也是传统的书画养生法。董其昌说:“画之道,所谓宇宙在乎手者,眼前无非生机。”就是这个道理。

万鸣的画风先是得之于天津,后与天津离,不同于天津的画风,也不同于北京,不同于全国,乃是他自己的画风。我曾给画家下定义:“风格的成熟,方可称为画家。”没有风格,不能算画家,风格不成熟,也不算画家。万鸣的画有风格而成熟,正而不邪,可谓真画者也!

万鸣画花鸟、走兽、人物,尤喜画猪,我看到他画了几十幅猪图。龚贤(半千)说:“物之不可入画者,猪也。”古人不大画猪,我查阅宋人的《宣和画谱》,在《畜兽门》中,画马多,画牛次之,画犬羊猫狸虎猿等皆有,唯没有画猪者。近人齐白石、徐悲鸿画猪,也只是偶尔为之。所以画猪者仍很少。万鸣画猪,一是把古人不画猪这个空白充实一下,二是他不忘本根。他生于农村,少时见到猪是常事,农家没有不养猪的,他对猪有特殊的感情。所以,他画猪尤下工夫,他画了一个长卷,上有一二十只猪。他画《田间》《悠哉》《踏青》《观秋》《秋意》等都以猪为主体。他画的猪也不同于齐白石、徐悲鸿等。他也是用元法化宋之法加之他自己的短戳笔法而画成,万鸣画的猪,不但画出猪之形状,猪之精神,更画出各种猪的特色和性情。这不仅是他的功力所致,也是他爱猪的精神所致。时人有曰:“齐白石画虾,徐悲鸿画马,黄胄画驴,李可染画牛,刘万鸣画猪,具得其神。”所言据实而合情理也!

绘画之成功,必历三境界:“始则神于好,中则精于勤,终则成于悟。”但路子正是关键。当然,路子也包括在“悟”之中。

万鸣认为,中国人画中国画,绝不能用西画替代中国画。西画的完善应由西方人去完成,西方人有西方的文化背景,中国人有中国人的文化背景,以西画替代中国画是非常无知且必然失败的方法。李可染也说我的画当然要再向前迈进一步,但不能迈到西洋画那里去。中国画自有伟大而高超的历史,继承中国画的传统,当然也可以适当吸收西画中可用之法,发展中国画,使之独立于世界艺术之林。用西画替代中国画,无疑泯灭了中国画,也损坏了西画。

刘万鸣坚持中国画的传统,并完善之,发展之,这条路是正确的。在刘万鸣的作品中,他求意,并始终强调造型的严谨和归纳。他画过大量的素描,有着严谨的西式造型方法,又呈现出中国式圆融而具内涵的造形理念。在他的中国画作品中,其将经典的西方绘画语言恰如其分地融入在画面之中,化之而生辉,巧妙而得体。万鸣非常推崇徐悲鸿的艺术,他认为作为绘画者自信的前提应具包容之胸襟。徐悲鸿画人物、花鸟、走兽,得体的造型,完美的中国精神,自然也有西方绘画语言在其中发挥著作用。所以徐悲鸿的作品有别于古人,这与他化西为中的理念是分不开的。万鸣有着正确的学术之路。在正确道路上发展,才能取得高超的艺术成就。

陈传席(中国人民大学博士生导师)(节选自陈传席《以古开今 高标新格》)

刘万鸣

1989年毕业于天津美术学院。

第十三、十四届全国政协委员,第十三届民盟中央委员、中国美术家协会副主席、中国国家画院院长、中国美术家协会中国画艺委会副主任、博士生导师、中国文化遗产研究院研究员。历任中国艺术研究院研究生院常务副院长、中国艺术研究院中国画院常务副院长、中国国家博物馆副馆长。

中宣部“四个一批”文化名家,享受国务院政府特殊津贴专家,中组部国家高层次人才特殊支持计划领军人才“万人计划”。中国画作品入选国家级展览,曾获得金、银、铜、优秀等奖项十余次,并被中国美术馆、中国国家博物馆、中国艺术研究院等国家级单位收藏。

Chinese Cultural Figures (Chief Editor: Wang Baosheng) All enduring masterpieces of painting must embody an unshakable “qi” (vital energy). In the traditions of the Song and Yuan dynasties, this manifests as three essential qualities: tranquil qi, pure qi, and rugged qi. A painter who remains steadfast in their artistic convictions will find no external distractions to disturb their mind. Through prolonged cultivation, inner serenity naturally emerges. Pure qi represents luminous integrity, and rugged qi embodies boundless vigor—both of which are exceedingly rare. The presence of tranquil and pure qi reflects an artist’s spiritual depth, while rugged qi reveals their technical mastery. This mastery originates from a profound understanding of traditional artistry. Only those with deep artistic cultivation can attain such rugged qi. I’ve observed many painters who lack a true understanding of tradition and pursue crude brushwork and vulgar techniques. The more they practice, the further they drift from authentic tradition, losing their artistic essence. Others, equally unenlightened yet lacking refinement, obsess over literal likeness. They force artificial color combinations and meticulous detailing, resulting in increasingly contrived and vulgar works. Neither approach constitutes genuine painting, let alone a path to excellence.

Liu Wanming’s paintings are characterized by rigorous composition, free-flowing brushwork, and profound inner depth with rich variations. Rooted in the traditions of the Song and Yuan dynasties, his works embody the meticulous precision and substantial weight of Song paintings, which achieve solemn grandeur in both form and spirit; while Yuan paintings showcase free-flowing elegance and scholarly refinement. Wanming’s creations harmoniously integrate the rigorous precision and majestic grandeur of Song paintings with the graceful subtlety and scholarly charm of Yuan paintings. He synthesizes the strengths of various schools into his own style, establishing a unique artistic identity. His paintings radiate a strong sense of tranquility, clarity, and rugged vitality. They present an ancient yet innovative aesthetic, representing a distinctive and substantial height in the development of Chinese flower-and-bird painting.

Liu Wanming’s mature painting style evolved through several stages of development. Initially, his works adhered to the popular painting techniques of the Song-Yuan tradition. For example, his early leaf paintings used bold ink strokes with varying shades, a technique he also applied to bird depictions. This style reflected his absorption of brushwork from Tianjin masters, as well as his own innovations. His linear compositions drew inspiration primarily from Yuan dynasty traditions. As a scholar-artist, Liu studied ancient painting theories and historical techniques. While he primarily followed the Northern Song masters, he believed the Southern Song works lacked vitality. Northern Song and Yuan paintings both rarely featured expansive ink washes—Yuan artists avoided both large-scale ink applications and heavy ink tones. Zhou Lianggong remarked, “Painting requires a balance of complexity and simplicity, focusing on brushwork rather than artistic conception. Northern Song landscapes are meticulously simplified, while Yuan depictions of withered branches and sparse rocks are densely packed.” Yuan painters employed dry ink techniques, creating fluid lines that mirrored calligraphic rhythms through controlled pressure and transitions. Though seemingly simple, these strokes contained boundless depth: “No single stroke is uncomplex.” Song painters’ mountain landscapes, such as Fan Kuan’s “Travelers by Streams and Mountains”, combined meticulous detail with understated simplicity. In contrast, Yuan artists elevated line work beyond Song standards. The late Ming literati disdained Zhe School painters for their emphasis on bold ink splashes over substantive content. Having studied Song-Yuan techniques, however, Liu Wanming mastered this paradox. His works preserved the rigorous form of the Song dynasty’s methods while achieving spiritual resonance. He employed Yuan-inspired brushwork that balanced looseness with suppleness. Grounded in profound stele studies, his calligraphic variations revealed a seamless integration of solidity and subtlety, creating richly layered compositions. His layered brushwork creates rich, weighty gradations. Using trembling-hammer strokes, he strikes a delicate balance between solid and void—no single stroke is purely solid or void, but rather exists in the interplay between them. This embodies the ancient principle of “solid strokes with void elements, and void strokes with solid elements,” a technique that demands exceptional skill. Wan Ming developed his distinctive artistic style through a profound understanding of these principles.

Wan Ming’s unique painting technique, which embodies the traditional philosophy of cultivating health through calligraphy and painting, involves neither excessive agitation nor meticulous detailing. Dong Qichang once remarked: “The essence of painting lies in the universe residing within the brush—every stroke brims with vitality.” This principle perfectly captures the essence of his artistic approach.

Wan Ming’s artistic style first took shape in Tianjin, then evolved beyond its boundaries. Distinct from the regional styles in Tianjin, Beijing, or even the national mainstream, his style ultimately became his unique voice. I once defined an artist: “Only when a style matures can one be called an artist.” Without an established style, one cannot be considered an artist, and without a mature style, one remains unqualified. Wan Ming’s paintings possess both distinctive and refined characteristics—upright yet unpretentious—and truly embody authentic artistry! His subjects range from flowers and birds to animals and figures, with a particular fondness for pigs. Having seen dozens of his depictions, I recall that Gong Xian’s (Banqian) famously remarked: “The most unpaintable creature is the pig.” While ancient artists rarely painted pigs, my research on the “Xuanhe Huapu” from the Song dynasty reveals a different pattern: horses dominated the “Animal Kingdom” section, followed by oxen, then dogs, sheep, cats, tigers, apes, and monkeys—yet pigs remained conspicuously absent. Modern masters like Qi Baishi and Xu Beihong only occasionally painted pigs. Thus, Wan Ming’s pig paintings serve dual purposes: filling the void left by ancient artists ‘silence and preserving cultural roots. Born in rural China, where pigs were ubiquitous, he developed a profound affection for these creatures. His most ambitious work is a long scroll containing over twenty pigs. Themes like “Field Scenes”, “Leisurely Days”, “Spring Outing”, “Autumn Reflections”, and “Autumn Aesthetics” all feature pigs as central motifs. Unlike Qi Baishi and Xu Beihong, Wan Ming’s approach blends Yuan dynasty techniques with Song methods, enhanced by his signature short-stroke brushwork. His depictions not only capture the physical forms and spirit of pigs but also vividly portray their unique traits and temperaments—a testament to both his artistic mastery and his deep-rooted love for these animals. As the saying goes, “Qi Baishi painted shrimps, Xu Beihong painted horses, Huang Zhou painted donkeys, Li Keran painted oxen, and Liu Wanming painted pigs, all of which captured the spirit.” What is said is true and reasonable!

A successful painting must go through three realms: “beginning with spiritual love, continuing with diligent work, and finally achieving enlightenment.” But the way is the key. Of course, the way is also included in “enlightenment”.

Wan Ming believes that Chinese people should never replace Chinese paintings with Western ones. Westerners should refine Western painting because they have their own cultural background, while Chinese people possess their own cultural heritage. Replacing Chinese paintings with Western ones is an ignorant and inevitably doomed approach. Li Keran also said, “My paintings must certainly advance further, but not to the level of Western art.” Chinese painting has a great and profound history. By inheriting its traditions, Chinese painting can appropriately absorb useful techniques from Western painting to develop itself, and establish its independence in the global art community. Replacing Chinese painting with Western painting would extinguish Chinese painting and damage Western painting. Liu Wanming insists on preserving, refining, and developing the traditions of Chinese painting, which is the correct approach. In his works, Liu Wanming pursues artistic conception while consistently emphasizing rigorous modeling and summarization. After creating numerous sketches, he uses meticulous Western-style modeling methods to present Chinese-style, holistic, and profound modeling concepts. In his Chinese paintings, he skillfully integrates classic Western painting techniques into the composition, creating luminous and harmonious works. Wanming highly admires Xu Beihong’s art and believes that a painter must embrace inclusiveness to be confident. Xu Beihong’s depictions of figures, flowers, birds, and animals demonstrate proper modeling and the perfect Chinese spirit while naturally incorporating elements of Western painting. Thus, Xu Beihong’s works differ from those of ancient masters and are inseparable from his philosophy of integrating Western elements into Chinese essence. Wan Ming has followed the correct academic path. Only through development along this proper path can one achieve sublime artistic accomplishments.

Chen Chuanxi (PhD supervisor, Renmin University of China) (Excerpt from Chen Chuanxi’s “Using the Ancient to Open the New and Set a New Standard”)

Liu Wanming

He graduated from Tianjin Academy of Fine Arts in 1989.

He is a member of the 13th and 14th National Committees of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), Member of the Central Committee of the China Democratic League (CDL) for the 13th term, Vice Chairman of the China Artists Association, President of the China National Academy of Painting, Deputy Director of the Traditional Chinese Painting Art Committee of the China Artists Association, Doctoral Supervisor, and Researcher of the Chinese Academy of Cultural Heritage. He has successively served as Executive Vice President of the Graduate School of the China National Academy of Arts, Executive Vice President of the Traditional Chinese Painting Academy of the China National Academy of Arts, and Deputy Director of the National Museum of China.

He is one of the “Four Batches” cultural celebrities recognized by the Publicity Department of the CPC Central Committee, an experts who enjoys special government allowances from the State Council, and a leading talent under the National High-Level Talent Special Support Program “Ten Thousand Talents Plan” by the Organization Department of the CPC Central Committee. His Chinese paintings have been selected for national exhibitions, and have won over ten awards, including gold, silver, bronze, and excellence prizes. His works are collected by national institutions such as the National Art Museum of China, the National Museum of China, and the China Academy of Art.

文化大家

文化大家