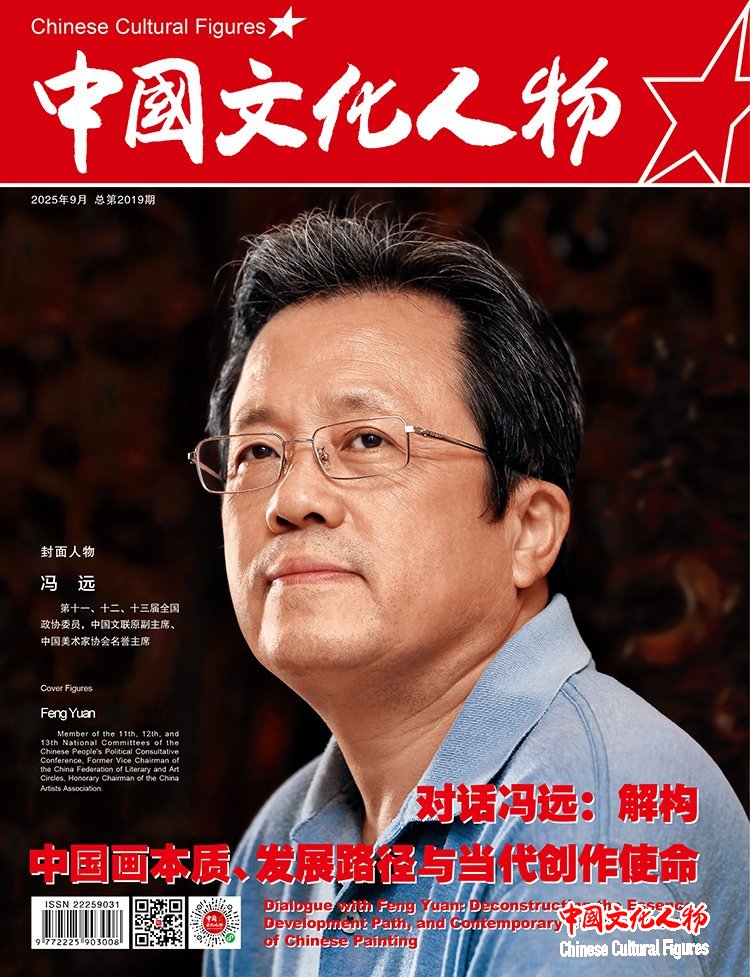

冯 远,第十一、十二、十三届全国政协委员,中国文联原副主席、中国美术家协会名誉主席

Cover Figures: Feng Yuan Member of the 11th, 12th, and 13th National Committees of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference, Former Vice Chairman of the China Federation of Literary and Art Circles, Honorary Chairman of the China Artists Association.

中国文化人物主编 王保胜/摄影报道

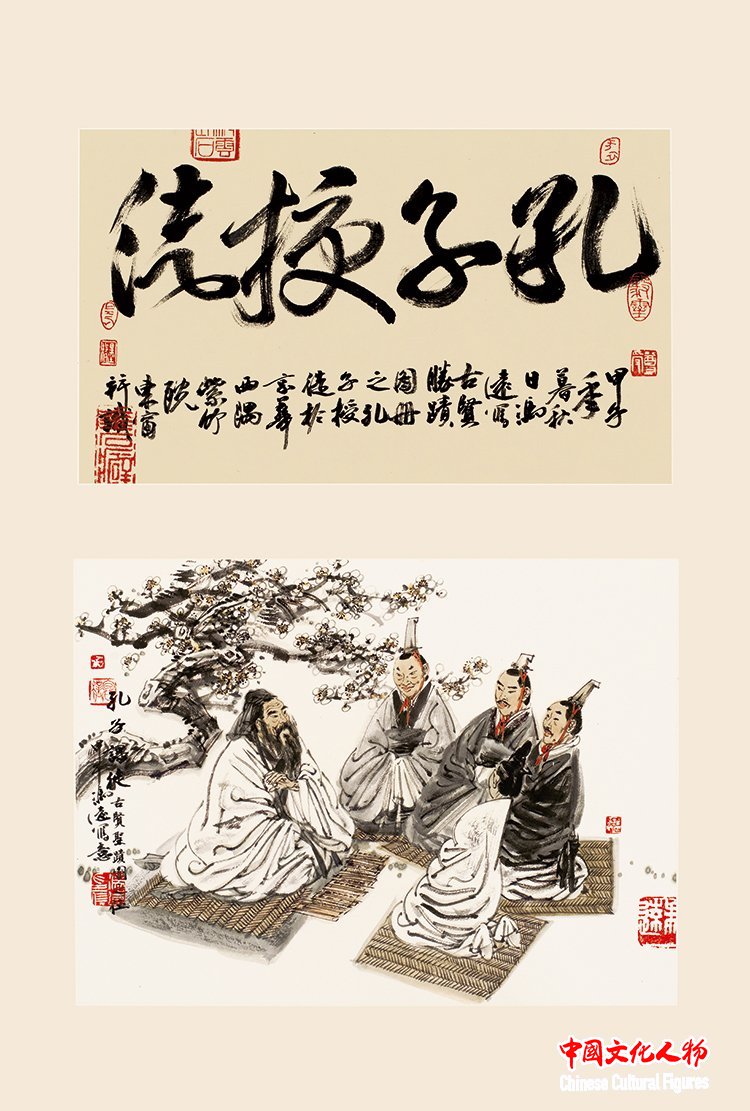

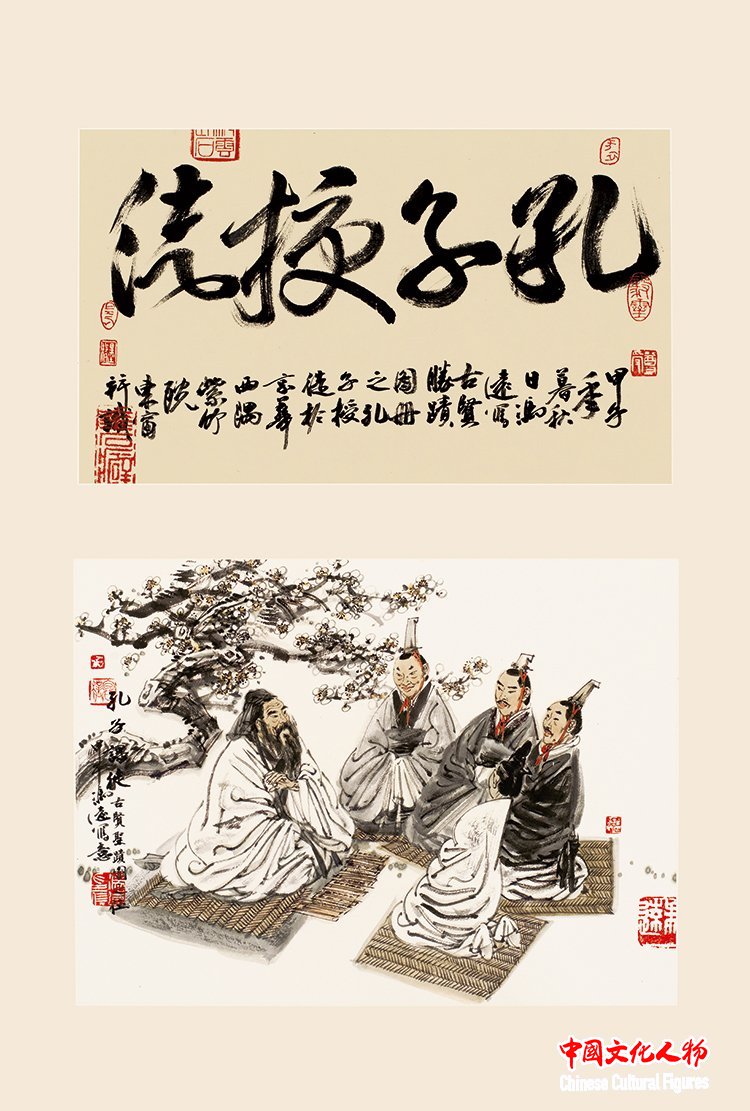

孔子授徒 58×82cm 冯远作品

“Confucius Instructing His Disciples” (58×82cm) by Feng Yuan

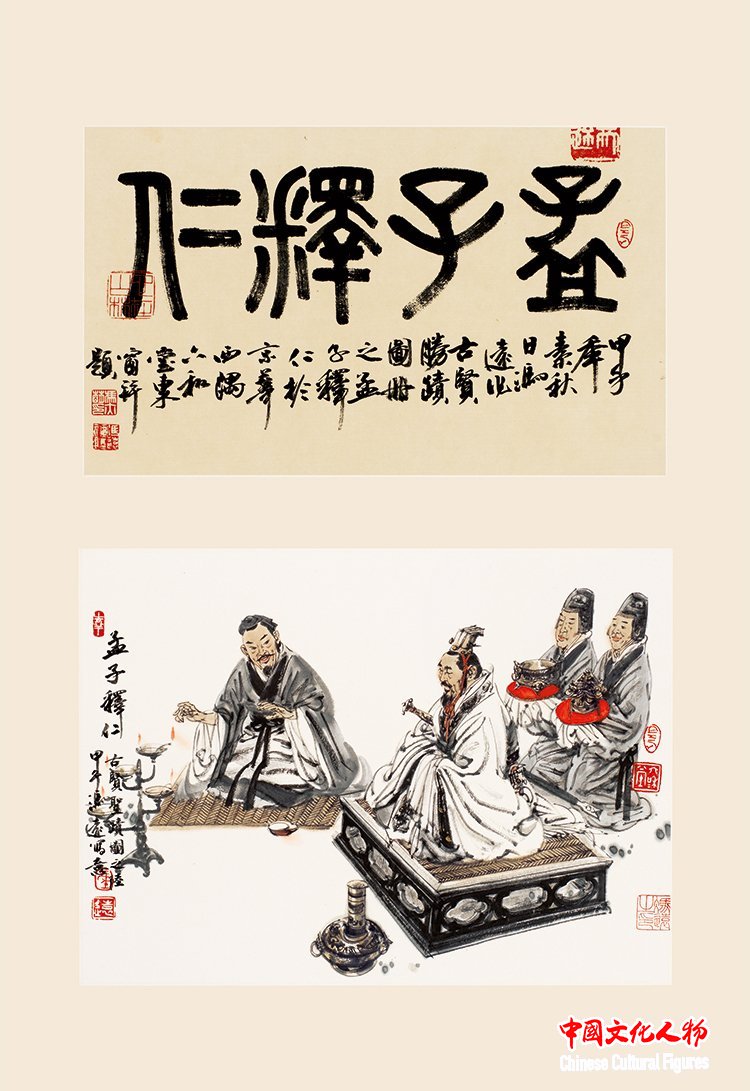

孟子释仁 58×82cm 冯远作品

“Mencius Explaining Ren" (58×82cm) by Feng Yuan

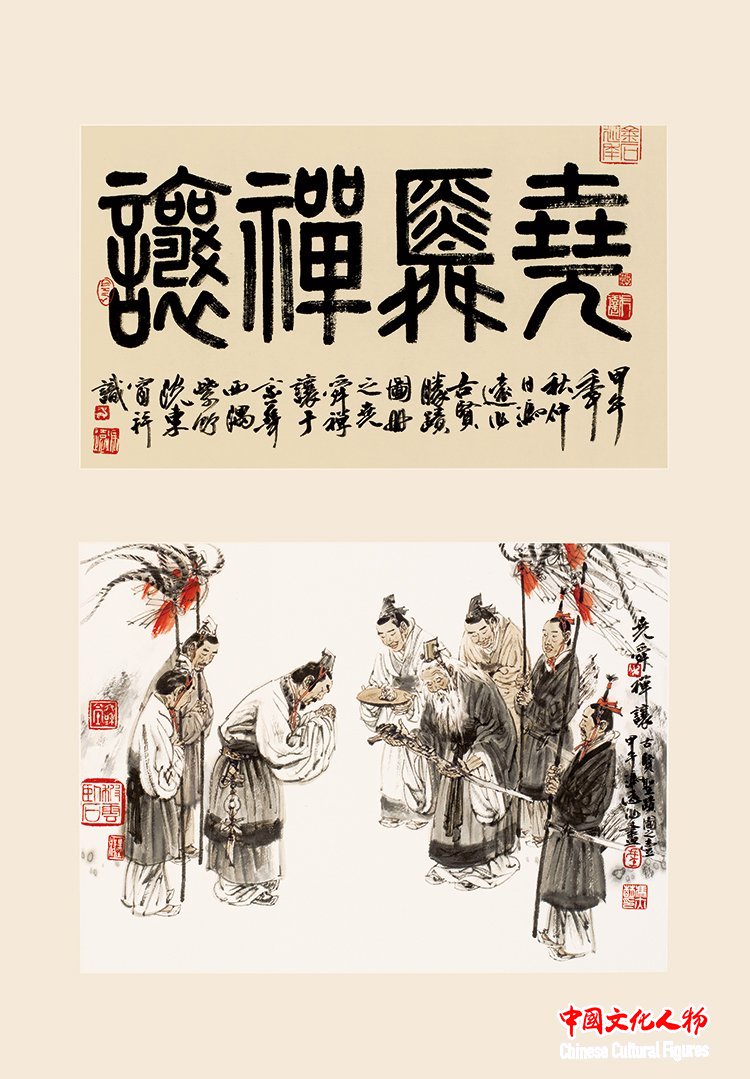

尧舜禅让 58×82cm 冯远作品

“The Abdication of Yao and Shun” (58×82cm) by Feng Yuan

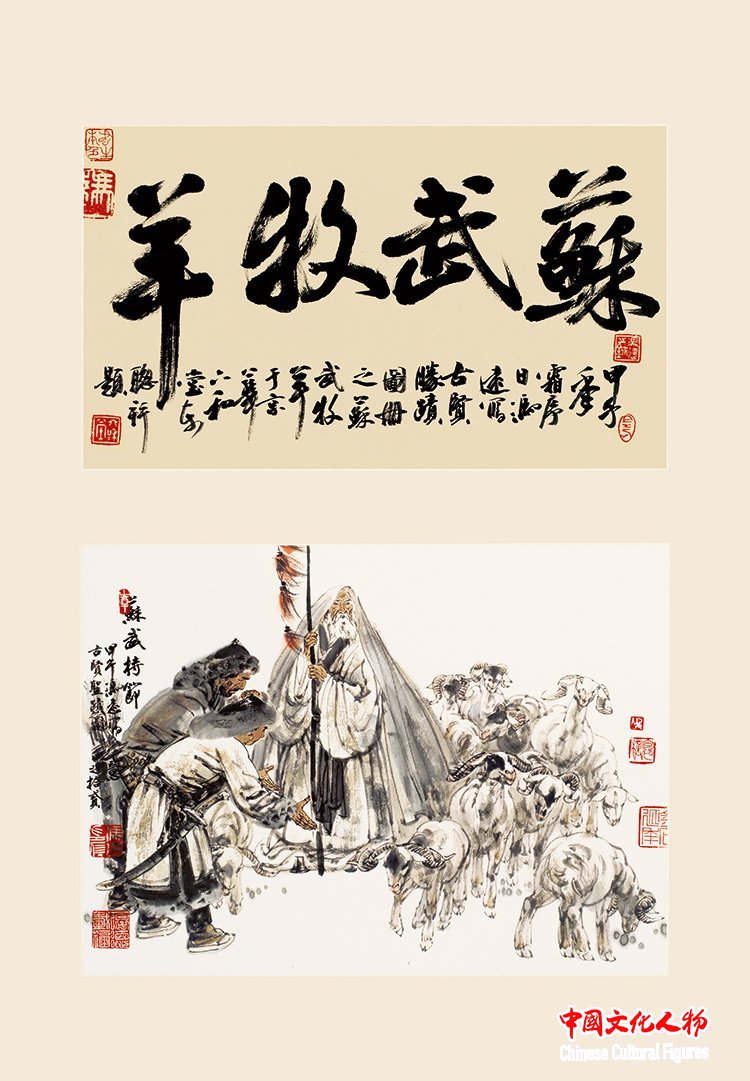

苏武牧羊 58×82cm 冯远作品

“Su Wu Herding Sheep” (58×82cm) by Feng Yuan

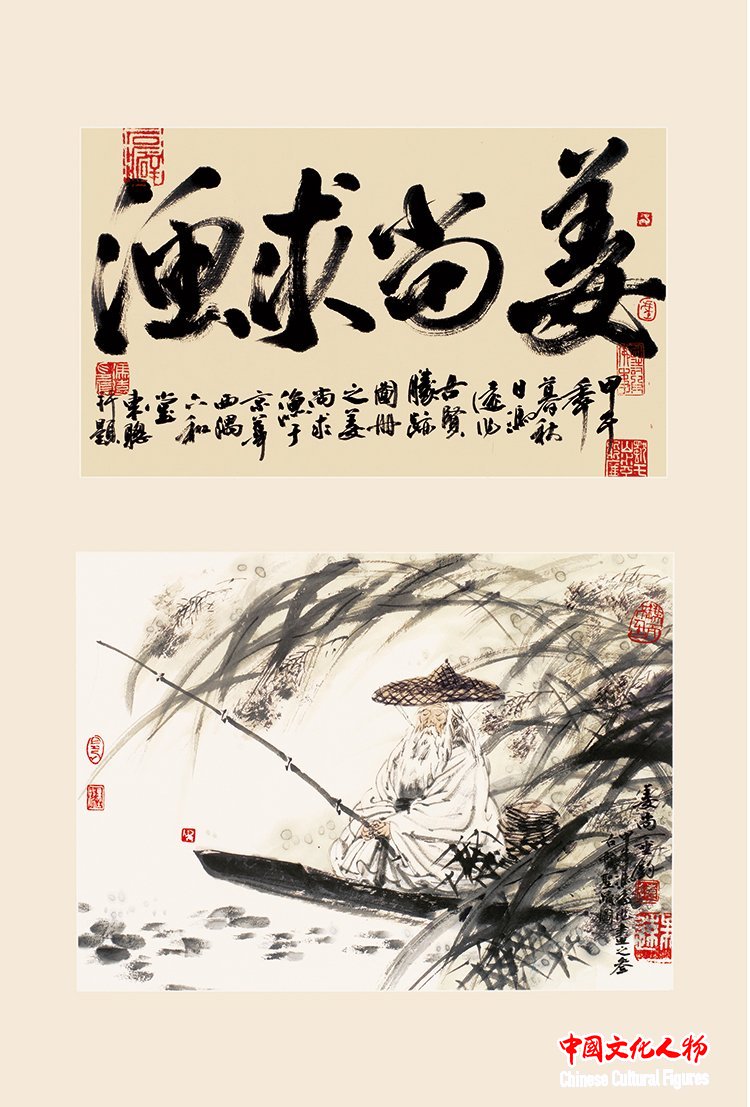

姜尚求渔 58×82cm 冯远作品

“Jiang Shang Seeking Fish” (58×82cm) by Feng Yuan

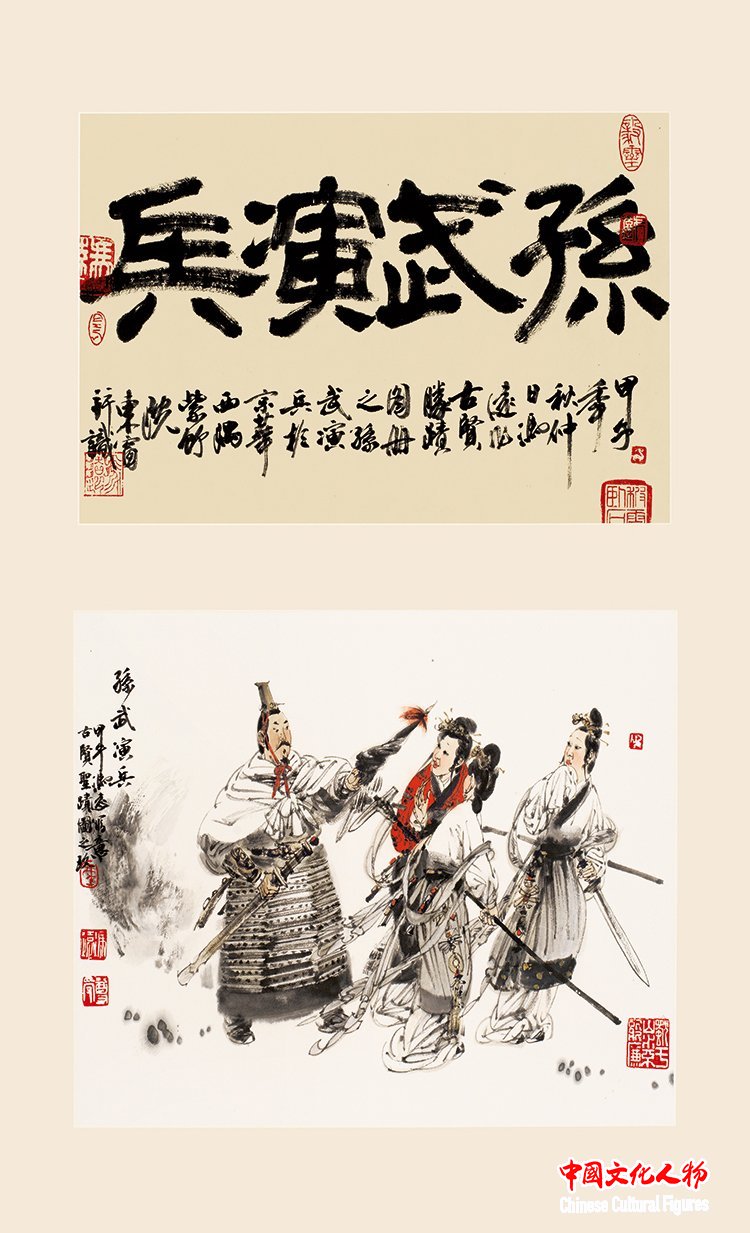

孙武演兵 58×82cm 冯远作品

“Sun Wu Drilling Troops” (58×82cm) by Feng Yuan

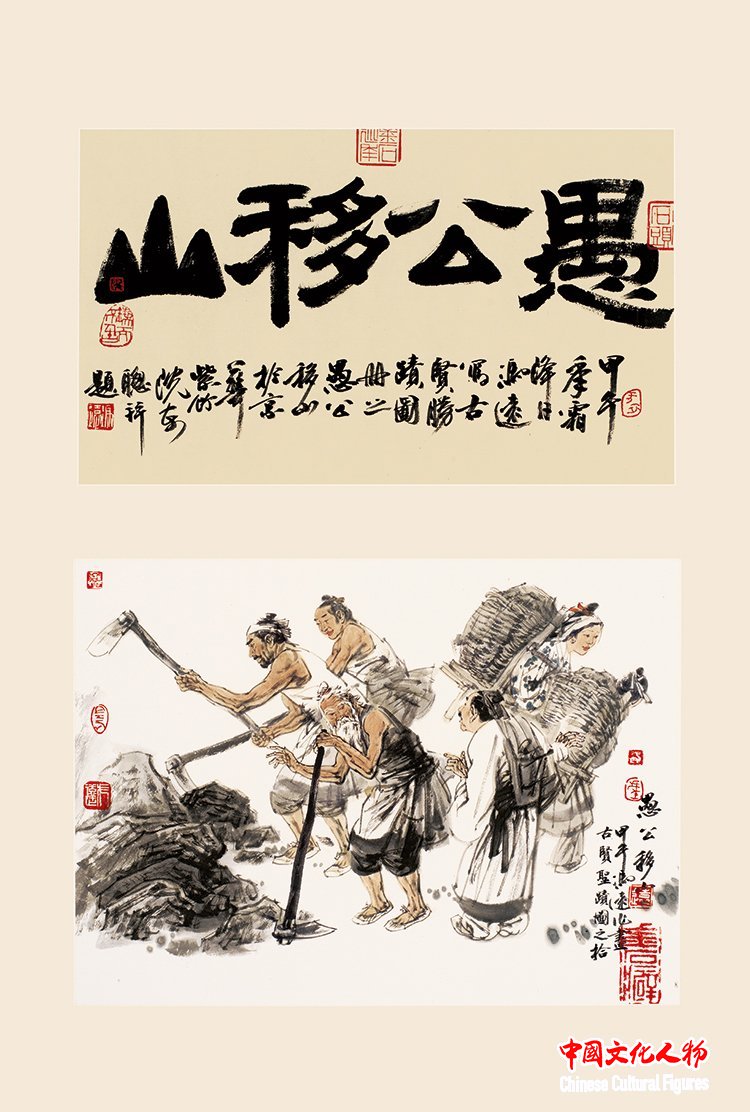

愚公移山 58×82cm 冯远作品

“Yu Gong Moving the Mountains” (58×82cm) by Feng Yuan

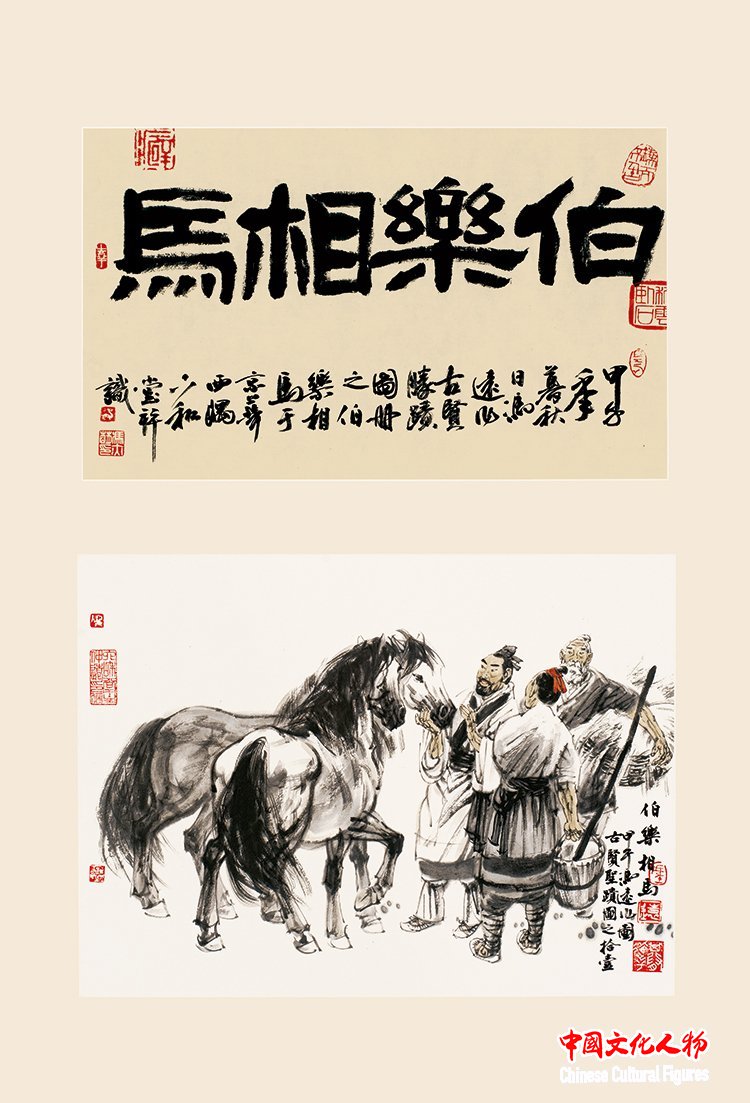

伯乐相马 58×82cm 冯远作品

“Bo Le Appraising Horses” (58×82cm) by Feng Yuan

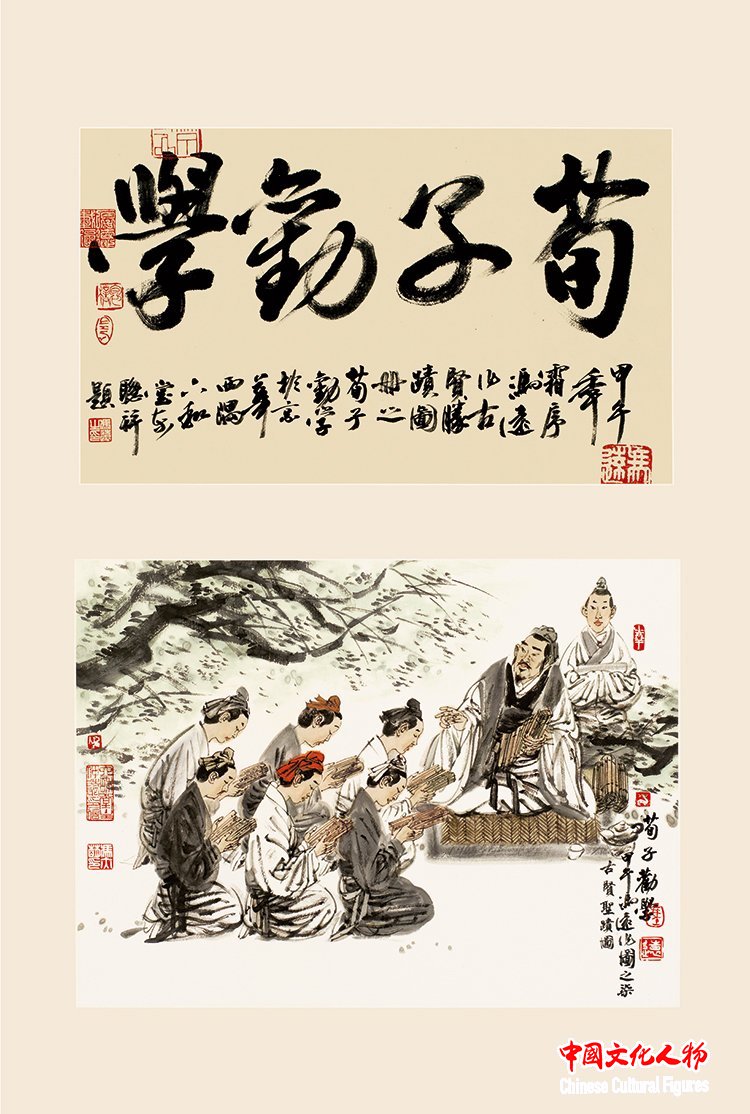

荀子劝学 58×82cm 冯远作品

“Xunzi Exhorting to Learning” (58×82cm) by Feng Yuan

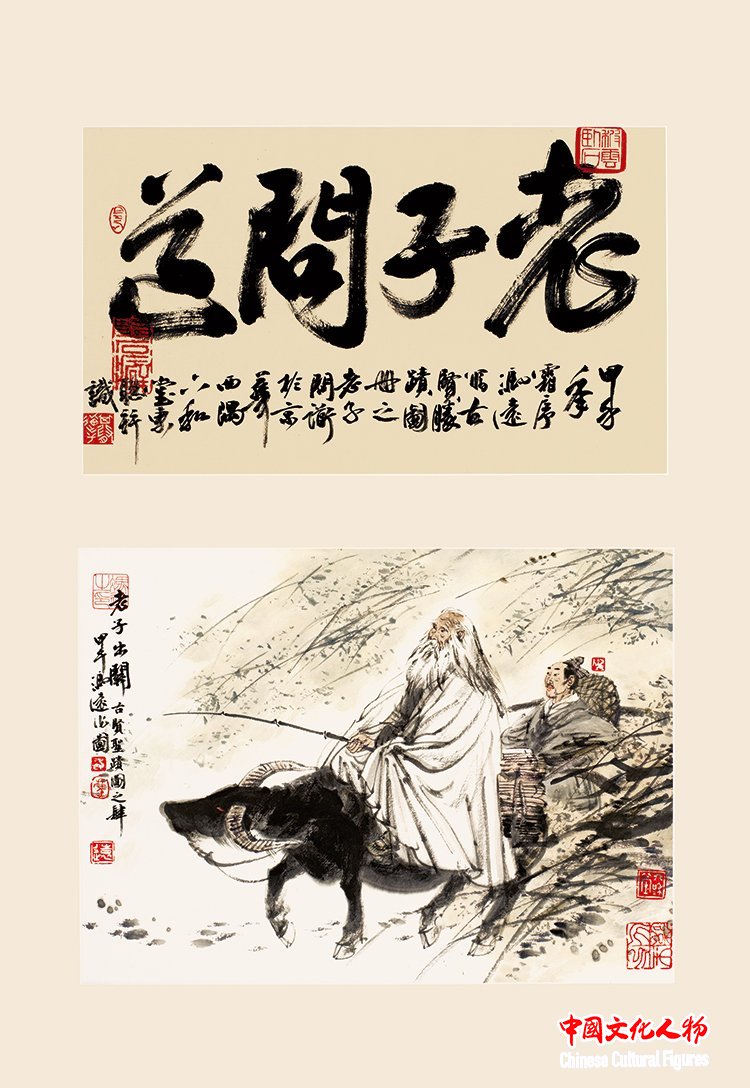

老子问道 58×82cm 冯远作品

“Laozi Seeking the Dao” (58×82cm) by Feng Yuan

什么是中国画?

冯远:如果从传统意义上来看,中国画是大家所熟悉的,画在宣纸、卷本上,以线造型、平面设色、散点透视、随类赋彩、汁墨当色……的绘画形式,到了宋代文人画兴起以后,又把诗歌、书法、篆刻融为一体,注重书写和水墨本身的丰富变化……当然,它背后包含了中国人文艺术精神、文史哲的综合学养和对中国的基本理解。从严格意义上来说,传统类型的中国画是指到明清为止的诗书画印兼容的艺术样式,包括工笔绘画、重彩壁画,比如说敦煌绘画,我们可以把它统称为中国画的基本样式。

19世纪末20世纪初,西洋美术的传入和专业艺术院校的陆续兴办,使学生们受到了严格的造型基本功训练,这为中国画的发展变革创造了条件,同时对传统绘画的研究也在循序渐进,今天我们能够读到真迹的这些作品都成为年轻人学习传统绘画的范本和基本功训练的一部分,所以学习中国画讲求从临摹入手,掌握传统绘画的技法;文化课、文史哲、诗书画,都是中国文化学养的重要部分。这两部分合起来才才是学的中国画的基础,也是由传统形态向现代形态转型的必修课。

中国画发展的三条路

冯远:西方20世纪以后,西洋绘画理念和外来艺术观念被大量介绍到中国,两种艺术在比较、交流、激荡、冲撞的过程中,互为补充。它的积极作用在于传统的样式在继承发展的过程中,经历了一个比较和选择的过程,并以此促进推陈出新、革故鼎新、自我变革。这个有难度,中国绘画历朝历代高峰林立,今天如果完全照搬下来,将难以超越。创新就势必在观念、技巧,包括图式上都要发生变化。比如说一件作品是一个限量,那么任何新元素的引入,就要剔出相当比重的旧有旧元素。所以任何一种变革和创新,它一定是在原有基础上,以个人实践的方式,做好弃与舍的选择。这是一条路。

第二条路,中西兼容。我们在世界美术史中都能看到,每一种变化,每一个新样式的出现,都是一种新的艺术观念引领。印象派、后期印象派、野兽派,再发展到后来的现当代艺术,实际上都是从观念、理念上发生的变革引发的。那么哪些吸收对我们来说是有益的,就要进行一番撷选了。学习不等于照搬,中体为用才是主心骨,所有的外来东西是要为我所用的,并和中国传统绘画中的基本要素达成契合,通过不断的比较、淘汰和实践,形成有别于中国古代传统的、又有别于世界各国其他绘画的样式,那才可能是中国自己新的东西。

当然还有第三条,把中国传统绘画解构了、打散了,把西方绘画原来古典主义以来的一些精华部分统统也都解构了。我们按照一种创新理念重新进行一番整合,形成一种全新的艺术。但破不等于立,立才是目的。所以我对中国绘画在未来的发展持乐观态度。因为现在中国有注重基本功训练的美术学院,每年都培养出很多年轻人。而且今天的年轻人对于研究中国艺术、中国文化、中国传统绘画的愿望和学习能力,包括物质条件、信息交流都要胜于古代,面对的考验只是怎么能够创造出新的艺术样式,又还是中国的。

创作的理想

冯远:造型的问题、色彩的问题、现实主义创作方法的完善问题、现代绘画的问题、精神内涵的问题等等,我曾经都在不同的创作阶段接受过检验。但今天来看,我觉得几乎没有哪件作品很满意。这个很奇怪,几乎画完每一件作品,放他一年两年再看,总会觉得很遗憾。如果某个地方、如果当初再怎么样一些就更好了。遗憾始终是有的,就是心里想象的那个图式始终是一个遥远的目标,虽然感觉就在你眼前,但实际上真正要达到,始终有距离。

作为一个实践者,我明白多少,理解多少,我尽量努力去做多少。我不能说我做的很好,但是起码我在这条路上去努力了。我争取让我的每一件作品,从构思尽可能投入我个人的丰富情感和我的人生阅历,尽可能去挖掘这个作品内涵和它背后的意蕴。在造型上,我当然是偏重于现实主义的创作方法,但是我又要丢弃那种纯写实的手法,把中国绘画的写意趣味融入进去。然后我要在抽象的笔墨与具象的造型之间,尽可能找到两者相契合的点,既能发挥笔墨,还要将笔墨跟色彩尽可能融合在一起,达到一种视觉上的和谐。

每完成一件作品,下一件作品我想的就是能不能有些新变化。我还是很欣赏毕加索说的那句话,“永远不要重复自己”,艺术家不是一个纯粹熟练的匠人,他应该有思想,应该有情怀和高超的艺术造诣,还有手头功夫。这样的作品才能够让观众感觉到你每一件作品中不同的情感、不同的样式、不同的联想,如果能这样当然是最好了,但实际上每个人都有局限,我也逃脱不了,我只能在某个阶段,尽努力去做好事情。

一张作品的使命

冯远:传统绘画里有相当多的人物画题材,但很难看到普通老百姓,看到大写的人。相当多的中国古典绘画是用来品赏藏玩的艺术,是在把玩笔情墨趣,用笔墨情趣表达胸中逸气。但是中国画要发展呀。原来的这些方法怎么表现今天改天换地的中国呢?

中华五千年的文明史,仅仅满足于小品、卷轴画、笔情墨趣行么?虽然也很重要,这是中国画精妙的一部分,但不能是全部,应该还要表现当今时代那些正大气象、社会进步和大的历史事件。传统的技法和结构样式不够用了怎么办?当然是要去创新,所以总书记说的“创造性的转化”“创新性发展”特别好!

转化是什么?原有的传统必须变,变成一种新的具有时代特征的形式语言,创新性发展就是创造发明了。这个“双创”实际上说的很明白,一个是求变,一个是创造发明。每一个时代都应该不一样,每一个时代都要有新发明、新创造才对,中华文明就向前发展了。特别是今天谈到中国式的现代化、现代文明、现代文化、现代艺术的创造,这个都是有创造发明和保持原有的基本特色的内涵在里面。

贺绚绚(中国文联美术艺术中心艺委会工作处副处长)

冯远

1952年生于上海。1978年入读浙江美术学院,1980年留校任教。

第十一、十二、十三届全国政协委员,历任中国美术学院副院长、文化部教育科技司司长、艺术司司长、中国美术馆馆长、中国文联副主席、清华大学美术学院名誉院长、中央文史研究馆副馆长、清华大学艺术博物馆馆长、上海美术学院院长、中国美术家协会名誉主席。

作品多以反映历史题材和现实生活为主,造型严谨生动,生活气息浓郁,绘画形式新颖,尤以擅长创作大型史诗性作品和古典诗词画意作品,出版有作品集、论文集、教材多种。近四十年来,其作品入选国家大型美术展览,获金、银、铜及优秀奖20余次,并被国内外众多美术馆、博物馆收藏。

What is Chinese painting?

Feng Yuan: In the traditional sense, Chinese painting is familiar to everyone. Painted on rice paper scrolls, it employs line-based modeling, flat coloring, scattered-point perspective, and genre-specific coloration, and ink-splashed coloration... After the rise of literati painting in the Song dynasty, the art form further integrated poetry, calligraphy, and seal carving. This emphasized the rich variations of brushwork and ink itself... Certainly, it embodies the humanistic artistic spirit of China, the comprehensive cultivation of literature, history, and philosophy, as well as a fundamental understanding of China. Strictly speaking, traditional Chinese painting refers to an art form integrating poetry, calligraphy, painting, and seal carving up to the Ming and Qing dynasties, including meticulous brushwork paintings and heavy-color murals such as Dunhuang paintings. These styles can be collectively referred to as traditional Chinese painting.

At the turn of the 20th century, the introduction of Western art and the successive establishment of professional art academies provided students with rigorous training in basic modeling skills. This created the conditions necessary for the development and transformation of Chinese painting. Meanwhile, research on traditional painting progressed step by step. Today, these authentic works have become part of young people’s learning materials and foundational training in traditional painting. Therefore, studying Chinese painting emphasizes starting with imitation to master traditional techniques. Cultural studies, literature, history, philosophy, poetry, calligraphy, and painting are all crucial components of Chinese cultural literacy. Only by combining these two aspects can one truly grasp the foundation of Chinese painting studies. This foundation is also required for transitioning from traditional to modern forms.

Three ways of Chinese painting development

Feng Yuan: After the 20th century, Western painting concepts and foreign artistic ideas were extensively introduced to China. Through comparison, exchange, interaction, and collision, these two art forms complemented each other. The positive role of this process lies in the fact that traditional styles undergo a process of comparison and selection during inheritance and development, thus promoting innovation, renewal, and self-transformation. This is challenging. Throughout Chinese history, painting has seen numerous peaks. If we were to completely replicate them today, it would be difficult to surpass them. Innovation inevitably requires changes in concepts, techniques, and even schematic approaches. For instance, if a work is limited in quantity, introducing a new element necessarily excludes a significant proportion of existing elements. Therefore, any transformation or innovation necessarily involves choosing which elements to abandon and which to retain based on personal practice within the original framework. This is the path we must follow.

The second path involves integrating Chinese and Western elements. In the history of world art, every transformation and emergence of a new style has been guided by a new artistic concept. For example, Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, and subsequent modern and contemporary art developments were all sparked by conceptual and philosophical transformations. Therefore, we must carefully select which elements are beneficial for our absorption. Learning does not mean mere imitation; the essence lies in using Chinese elements to serve practical purposes. All foreign influences should be adapted to our own context and harmonize with the fundamental elements of traditional Chinese painting. Through continuous comparison, elimination, and practice, we can develop styles that differ from China’s ancient tradition and stand apart from other global artistic expressions. Only then can these styles truly represent China’s new identity.

Of course, there is a third point. We have deconstructed and fragmented traditional Chinese painting and dismantled the essence of Western painting since the classical period. Through an innovative concept, we have reintegrated these elements to form a completely new art form. However, breaking things down does not equate to building something new. The ultimate goal is to establish something new. Therefore, I am optimistic about the future development of Chinese painting. Currently, China has art academies that emphasize fundamental training and nurture many young talents each year. Moreover, today’s youth possess greater aspirations and are more capable learners than their predecessors when it comes to studying Chinese art, culture, and traditional painting. Their material conditions and access to information surpass those of ancient times. The challenge they face now lies in how to create new artistic styles that remain authentically Chinese.

The creative ideal

Feng Yuan: Throughout my creative journey, I have tested the limits of form, color theory, refining realist techniques, modern painting conventions, and spiritual depth. Yet, looking back today, I find that few of my works truly satisfy me. Whenever I revisit completed pieces after a year or two, lingering regrets inevitably surface, and this paradox persists. There’s always room for improvement. What I envisioned as the ideal formula remains an elusive target. Though it seems within reach, achieving that vision always feels perpetually distant.

As a practitioner, I strive to understand and comprehend as much as possible, and to do as much as possible. While I cannot claim to have done well, I have at least striven on this path. I strive to infuse every piece I create with my rich personal emotions and life experiences from the initial conception, exploring the depth of each work and its underlying implications. In terms of form, I naturally lean toward realistic creative methods. Yet, I also discard purely realistic techniques to integrate the freehand charm of Chinese painting. Then I seek to find the point of convergence between abstract brushwork and concrete forms. My aim is to express brushwork and harmonize it with color to achieve visual harmony.

After finishing a piece, I always wonder if my next one can introduce new elements. I deeply admire Picasso’s timeless maxim, “Never repeat yourself.” To transcend mere craftsmanship, an artist must possess intellectual depth, emotional resonance, artistic mastery, and technical proficiency. Only through such dedication can a work truly convey distinct emotions, stylistic variations, and layered interpretations. While this ideal remains admirable, we all face limitations. At any given stage, I strive to do my best within these constraints.

The mission of a work

Feng Yuan: Although traditional paintings often depict figures, it is rare to see ordinary people or grand depictions of them. Many classical Chinese paintings are created for appreciation and collection, embodying the artistic sensibilities through brushwork and ink techniques that express a free spirit. However, Chinese painting must evolve. How can these traditional methods represent today’s transformative China?

Has China’s five-thousand-year civilization been confined to miniature paintings, scroll artworks, and calligraphy? While these remain vital components of Chinese artistry, they should not dominate the narrative. Contemporary expressions must capture the grandeur, social progress, and pivotal historical developments of our era. When traditional techniques and structural frameworks prove inadequate, innovation becomes imperative. This is precisely why the President’s concepts of “creative transformation” and “innovative development” are so significant!

What is transformation? Traditional forms must evolve into new forms of language with contemporary characteristics. Innovative development essentially means creation and invention. The “Mass Entrepreneurship and Innovation” initiative clearly articulates two aspects: seeking change and fostering innovation. Each era demands distinctiveness, requiring new inventions and creations to propel Chinese civilization forward. Particularly in today’s discourse on modernization with Chinese characteristics, modern civilization, cultural innovation, and artistic creation, these concepts inherently encompass creative breakthroughs and preservation of fundamental cultural traits.

He Xuexuan (Deputy Director of the Art Committee Working Office, China Federation of Literary and Art Circles Art Center)

Feng Yuan

He was born in Shanghai in 1952. In 1978, he enrolled in the Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts, where he later began teaching in 1980.

He is a member of the 11th, 12th, and 13th National Committees of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC). He has successively served as Vice President of the China Academy of Art, Director-General of the Department of Education, Science and Technology of the Ministry of Culture, Director-General of the Department of Art of the Ministry of Culture, Director of the National Art Museum of China, Vice Chairman of the China Federation of Literary and Art Circles (CFLAC), Honorary Dean of the Academy of Arts & Design, Tsinghua University, Deputy Curator of the Central Research Institute of Culture and History, Director of the Art Museum of Tsinghua University, Dean of the Shanghai Academy of Fine Arts, and Honorary Chairman of the China Artists Association.

His works predominantly focus on historical themes and contemporary life. They feature meticulous yet vivid compositions that capture the essence of daily life. Renowned for his innovative painting styles, he is particularly distinguished by his expertise in creating large-scale epic works and classical poetry-inspired paintings. He has published multiple collections, including art portfolios, academic papers, and teaching materials. Over the past four decades, his creations have been selected for major national-level art exhibitions, earning him over 20 awards, including gold, silver, bronze, and excellence prizes. His works are now part of the permanent collections of numerous art museums and galleries, both domestic and international.

文化大家

文化大家